One of the most important tools when developing software is a good development environment, called an IDE (Integrated Development Environment), with at least an editor, build functionality, debugger, and being able to go directly from a compile error listed in the compiler output to the broken part of the code.

On Windows, my primary tool for this is Visual Studio, although I also use Eclipse for some projects, mostly involving scripting.

For the past few years, I’ve been using Visual Studio 2019, the then current version, but a few months ago I started using the newer 2022 version. Unfortunately, I quickly discovered that I can’t really use it for my major work task: Getting Vivaldi to build again after a Chromium upgrade, because important functionality broke in that version. The result is that I am back to using VS 2019 for that task.

When I am recompiling Vivaldi after a major Chromium upgrade (a process that can take several days), there will be a lot of compile errors (mostly due to changes made by the Chromium team no longer with our own code) that will need to be fixed, and it is very useful to be able to just click on the compile error and get to the exact line in the code where the problem was encountered.

Both VS 2019 and VS 2022 have this functionality, but in VS 2022 it is partially broken, to the extent that it is unusable for a major operation like getting an updated source base to work again, with 100+ files failing to build properly.

The problem is that, while VS 2022 opens the correct file, it doesn’t open it in the “right” way.

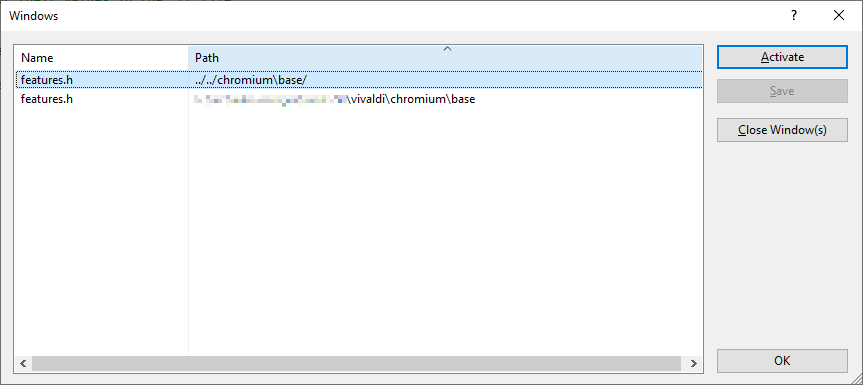

The compile error output writes the filename location as relative to the build directory (in my case out/Release), e.g. ../../chromium/chrome/foo.cc, and VS 2022 opens it with that path, relative to the build directory, not using the absolute path drive:/src/project/chromium/chrome/foo.cc which it uses for files opened any other way, as you can see from the screenshot at the top.

It may be that Visual Studio’s own compiler always prints the absolute path in the compile errors, which might explain how this issue was not discovered in testing, but Chromium-based projects no longer use that compiler to build Chromium, they use the LLVM Clang compiler, which outputs relative paths to the file with the error.

The result is several problems, first of all, there can be two tabs open for the same file, and this means that you won’t have access to the edit history of the other file, and having multiple tabs supposedly viewing the same file is a problem if the tabs are out of sync with each other.

Second, these extra tabs are not integrated into Visual Studio’s “Intellisense” system, which parses the code, indicating errors, and can be used to find definitions of functions and classes. Although … Intelllisense no longer works even close to as well as it did 20ish years ago, in Visual Studio 6, in fact using Find in File works usually better.

As mentioned, opening the code in a tab works well in VS 2019, so something got broken along the way between VS 2019 and VS 2022. Probably there is only a call to a function or two to create an absolute path of the file path that is missing.

I reported this issue in June to MS via two of their Twitter accounts as reporting bugs via Visual Studio requires that you log into the system, which requires an account, and I don’t create new accounts at the drop of a bug (or shoe), I generally only do so when I am going to actively use the account for several years. In any case, reporting a bug should not require an account on the system.

As far as I can tell from searching the Known Issues list (using its bad search engine, they might want to talk to some search engine developers) for Visual Studio, my report had not been added a few weeks ago.

However, this is not the only problem with VS 2022.

Among the reasons for moving to VS 2022 was that it is now built as a 64-bit executable, not a 32-bit like before, which should make it better able to manage gigantic projects like the ones based on Chromium. The full Chromium project (even Vivaldi’s relatively lightweight one which does not include all support sub-projects) consumed so much memory when loaded in the old 32-bit VS 2019 that it tended to hit the 3 GB RAM roof and crash, especially in the middle of debugging an issue. A 64-bit executable should be able to handle much larger projects as long as the machine have enough memory installed (and mine have 128 GB RAM).

Unfortunately, VS 2022 does not seem to be very stable at present and has even crashed while being idle in the background (that is, it crashed even if you were not looking at it the wrong way), although I am not sure if that is still the case after the most update, although it still crashes at times.

In other words, at present Visual Studio 2022 is a major disappointment.